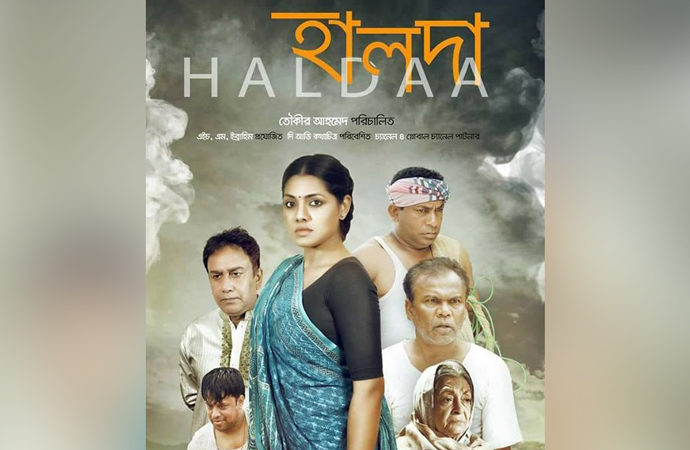

Our hopes run high when we see Bangladeshi directors making worthy attempts at combining urgent social issues with visual aesthetics. Such a film is Haldaa, directed by renowned media personality Tauquir Ahmed, released in December 2017. But what actually makes a film a film? There are subtle differences between making a drama on-screen and a film on the screen. Critically speaking, Haldaa might be a “good” production in terms of concept and story, but is it a “good” film in terms of cinematic aestheticism?

Before making a film, the foremost task is to come up with a concept. Here, Haldaa passes with flying colors. A concept based on the river Haldaa, flowing through Chittagong, connecting tales. On the lives of fishermen and their daily affairs, and dealing between the lines with “climate change”. Because of unbridled industrialization, boosted by capitalism, in areas linked to the Haldaa. The film thus addresses the burning issue of global warming!

The next stage is storytelling. What story should tell to market this critically grave global issue? Considering Bangladeshi viewers’ predilection for stereotypes – in Bangladesh art presumed to. “Entertaining” as opposed to illuminating – what could serve better than a love story?

The story in this film projected through characterization and the actions of the characters create the ups and downs in the plot. Hasu (Nusrat Imroz Tisha), daughter of Monu Miah (Fazlur Rahman Babu), is in a relationship with Badiuzzaman (Mosharraf Karim) who works as a fisherman with Monu Miah.

Sometime in the Past

Sometime in the past, Hasu’s family was in serious debt after pirates seized their fishing boat. So, Hasu gets married to Nader Chowdhury (Zahid Hasan), an influential owner of a brick-field in the locality. Meanwhile, Nader’s family is eagerly waiting for a baby – an expectation that Nader’s first wife Jui (Runa Khan) could not fulfill.

This primary plot where predictability at a peak, though the director tries to present the screenplay in a way as if actions are being revealed in one layer after the other to attempt cinematic suspense! However, outstanding performances by the actors/actresses is what actually takes viewers in.

Speaking analytically about characterization, it can say that the characters have pulled off the Chittagonian dialect without a hitch. As far as Badi is concerned, he is a responsible fisherman who joins the Haldaa River Saving Committee and certainly does not forget his love affair.

On the other hand, Nader Chowdhury unveiled gradually as a “villain,” depicted as the “king”. Who can buy “mother hilsa,” though it is illegal! For many working-class people, such actions haunt them as the ultimate “sin,” as is the case for Monu Mia, Hasu, and Badi.

The other character, who’s actually the protagonist, is Hasu, whose versatility helps the plot move ahead. She projected as bold, resilient, and revolutionary, rather than as a stereotyped woman. She can speak against authority figures. Nader’s mother Surat Banu is an example, against whom Hasu spoke up in a scene. When hilsa served at dinner to guests, high-ranking government officials.

If, like the story, each framing arranged with an aesthetically rational reasoning and theoretically connected with the issues portrayed, the visual aesthetics would have able to balance the suspense it wished to create, rather than so predictable.

Symbolically

Symbolically, the director tries to thread pregnant Hasu, productive river Haldaa, and mother hilsa along the same line as they all victimized by Nader, a representative of industrialization. This parallelism captured well in their names as all three starts with an “h”. However, in terms of visual storytelling, the thread seems loosely attached and here visual presentation loses its convincing connection. Nevertheless, in the end, Hasu frees herself, along with the Haldaa, from the clutches of patriarchy and profit-mongers by killing Nader with the strike of a “zamindari knife.”

Yet, a few incidents might seem quite contrary to Hasu’s rebellious attitude. For instance, she agrees to save her family and pay off their debt by accepting a large amount of dowry money (den mohor) from Nader before getting married.

Secondly, as a wise character, how can she decide to elope with Badi knowing that Nader’s people, sooner or later, will hunt them down? Probably, such an unwise decision was deliberately scripted for Nader to take his revenge by burning Badi alive as Nader is certain that Badi is the father of the child in Hasu’s womb.

As for the screenplay, it not tightly crafted either. However, some of the visuals well-knitted through the lens. For instance, viewers learn about the “dream-hut” of Hasu and Badi, and within seconds, an existential crisis shatters the hut with the timing of her consent to marry Nader. On seeing her father becoming ill due to an economic crisis, Hasu swiftly changes her mind.

Having a Good Concept

Despite having a good concept, story, and characterization, the cinematography makes the film lose its cinematic look. Done by Enamul Haque Sohel, the cinematography in most of the sequences cannot strike a chord with us. It lacks detailing since the shot-division seemed to poorly planned, which caused the visual aestheticism in the film to fall.

If, like the story, each framing was arranged with aesthetically rational reasoning and theoretically. Connected with the issues being portrayed, the visual aesthetics. Would have able to balance the suspense it wished to create, rather than being so predictable.

However, editing and color grading, done by Amit Debnath, well-balanced, keeping pace with the tone of the film. Nature ruined by human greed backed up by industrialization. Even the music, directed by Pintu Ghosh, is connected to the mood.

The most aesthetically as well as theoretically enriched scene in this film the before-the-death dialogue of Surat Banu. This is the first time she shares her name with Haus. A markedly feminist consciousness rises up in their conversation: Women hardly called by their names once they become mothers.

Nature exists as a force which has an impact on human evolution. So, through the lens. This film attempts to speak about how human culture connected to the physical world. Just wishing that Tauquir makes the attempt to be spontaneously convincing, rather than seemingly forcible, in his future cinematic presentation!

Viva La Arts, Viva La Films!